|

Dr. Bridget A. Teboh is brilliant; she is a delightful person, a respected scholar, is committed to the study of women and gender, and the education of all students. A full professor of History at UMass-Dartmouth, she holds a Ph.D. from UCLA, a B.A. (combined honors) in English and French from the University of Cameroon, Yaounde, and a DUEF, (Diplôme Universitaire d’Etudes Françaises) from Université Lyon III Jean Moulin in France. Dr. Teboh is an expert in African History, African-American Women’s History, Women’s and Gender Studies, and related subjects. She is a two-time awarded scholar of the Carnegie ADFP, an editor and author of more than 30 works. Other achievements include; the presentation of 65 professional papers at national and international conferences and has been featured on numerous radio and television programs. We had the pleasure of speaking with Dr. Teboh as the fall semester was winding down. She was charming, enlightening, and knowledgeable about an array of topics, always able to look beyond the noise of controversy and get to the heart of the subject. It is our pleasure to share our conversation with such an amazing woman. Steven: What was your mission or the objectives during your recent visit to Nigeria, and what were you charged with doing?

Bridget: My last visit to Adeyemi College of Education, was a follow up on Carnegie African desk, for fellowship program activities. Those activities are curriculum development, research collaboration, and graduate student mentoring and teaching. I was charged by Carnegie to follow up on a project that already started in 2017. It is at the College of Education Center, a center for Women’s Studies and known as the Directorate of Gender and Sustainable Education. It’s a new center approved by the federal government of Nigeria. My responsibilities were to set up a program and to co-develop the curriculum and courses; however, because I’m also an historian, I shared duties with the history department to update their curriculum and mentor their graduate students. Many days included lecturing, because I couldn’t be on campus and ignore students with courses they were struggling with; one was on American Reconstruction. I also worked with junior faculty, that is, new lecturers to the college. They too would benefit from training because the resources are not there. My workshops were for junior faculty and other post-doctorates and included how to write grants as well as publish articles. Steven: It sounds like the work was multifaceted. Bridget: It was, and, even though I was there for Carnegie, their core activities are specific; it was necessary to develop curriculum, core development, research collaboration, graduate student teaching and mentoring. It was a tremendous amount of work. Steven: Tell us about your experiences. Bridget: I am from the Cameroons, and it is the only bilingual country in Africa. In the sense that the official language is English and French, on the campus of Adeyemi College of Education, they have the French department without lecturers. While there, a part-time lecturer came to meet me and asked if during my spare time, I could have a conversation with the students because that would allow them to speak French. With this request, I soon realized I would be pulled in many directions. Steven: So, educational opportunities kept arising? Bridget: Educational opportunities kept arising, and I couldn’t say no. Steven: How did Gender Studies and Women’s Studies fit into your assignment? Bridget: The fact I had to set up the center was a big boost for the campus and community. Dr. Oienebu Martina (from the university) and I, had a chat one day, and she told me that my presence on campus was startling; she explained that “Everybody calls you madam gender.” Normally, when they call you madam gender in Africa, it’s not a good thing because that means the men are not happy. They think you want to seize power or authority from them and so they’re looking at you as undesirable—a person who is going to compete with them negatively. She went on to say, “You being here has everyone’s respect, and they want you to talk to them and their classes; they want to hear about gender. You have no idea the shift in thinking that is occurring!” Steven: Who was this group? Bridget: The faculty on campus. Steven: All of them? Bridget: Both men and women, with the students hesitating whether it was a good thing to have a Women’s Gender Studies program on campus at first. With this uncertainty, I told them that all good schools are supposed to have a Women’s and Gender Studies program. In Nigeria, I think there is only one program for the four campuses. Nigeria is a huge country. It’s not a good thing to have only a single course. You have women in development, women in parliament, with everybody screaming, “gender segregation.” This is where problems begin. Steven: Is there an issue of militant activism over gender differences? Bridget: Few people do come off like that—very radical. I think there is a difference between how Women’s and Gender Studies are perceived in America and Africa. Steven: Could you address that. Bridget: In America, when you talk about women and gender, it goes in many directions, and it ends up being male-bashing. All kinds of things that occurred in the 70s and 80s. It’s not about that for Africans and African women, even in rural areas they tell you when we talk about gender. The people speak about a complimentary existence before colonization—which disrupted everything. Life was simply; I can’t exist without you. You can’t exist without me. Now, if you married me and I have to carry your child, you will not be the one to push that baby out. I will be the one to push the baby out. But you have to support me because it’s our baby. Because we are partners, we have to work together for the good of our home and community. It is what gender is about. The issue behind discourse is perception, believing that we are pushing on the African government and society, for change stems from the interpretation and occurrence in the West. I made sure that I explained to people that what we are doing there is good. Something that is going to benefit both men and women. So, when we say, Women’s and Gender Studies program or Women, Gender and Sexuality, it’s not just for women because then you would be preaching to the choir; it is about men too and how to jointly exist. Steven: Have the students you taught, already cemented their bias? And, if so, can they be re-educated? Bridget: I think the answer to both questions is yes. Steven: How do you solve that dilemma? Bridget: The classes are male and female, just like we have here. When I taught Women and Gender in Africa, half the class were young men, and the others were women. Gender should not segregate; it means male and female; when you sit in a classroom, you discuss all kinds of things; abuse, violence and equality. I try to give real-life examples and show how foolish it would be to grade people differently or show preferences because of their sex. I explain that hard work equals opportunities for everyone. In Africa, the tide is changing rapidly, people realize what is happening, even though only half the population is educated. Many issues are generational and unfortunately have to do with property and inheritance. There are many land disputes between adult children. Only recently have people, both literate and illiterate, begun to educate themselves. By making sure that if you have four children, property and its use should be spread across equally; this is how improvement is made. Steven: What other issues come to mind? Bridget: In the last 20 or 25 years, it’s been gradually changing for the better because we’ve had incredible scandalous burials and funerals of “big men.” When you talk about wealth in Africa, you talk about politics. You talk about how important people have always been men. Steven: Coming back to the US, if you were to suggest how things could be better regarding gender, what would be your suggestion? Bridget: In the US, things are improving for the better and some good laws and policies are in place. The problem is implementation. Just like in Africa, the biggest issue is implementing those good laws that you have on books. If you see African governments and their constitutions on paper, you would want to go there in a minute. Brilliant. Everything is there, but it lacks follow-through. Steven: What do you believe was your greatest success during this last trip? Bridget: I think one of my greatest successes was becoming an informal US Ambassador to Nigeria when people came to me with questions out of the blue and had nothing to do with Carnegie activities. Carnegie is doing a brilliant job, the African Diaspora Fellowship Program is for scholars to undertake education, and projects in Africa, but it also allowed me the freedom to expand my distribution of resources to people who will benefit, while also aiding the continent. Steven: What else did you learn? Bridget: A funny thing; when I asked people what they wanted to know most about America, they would ask me, “Is it true that there’s a lot of dollars in America?” My response was, “Yes, there’s a lot of dollars, but you don’t collect it on the street or pluck from trees. You have to work day and night.” I consider myself lucky or blessed that I only have one job and my work fulfills me. But I have friends and colleagues who have three jobs, and I explained this to students. Steven: Will you return to Africa? Bridget: I will go back; I’m going to apply in April for a summer visit, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. Steven: Do you have any other plans? Bridget: I’m hoping we can work out collaboration with students. Our campus is willing and capable of hosting students. I hope we can visit this idea at some point in the future. Steven: Thank you, it has been gratifying to speak with you. Bridget: Thank you so much.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

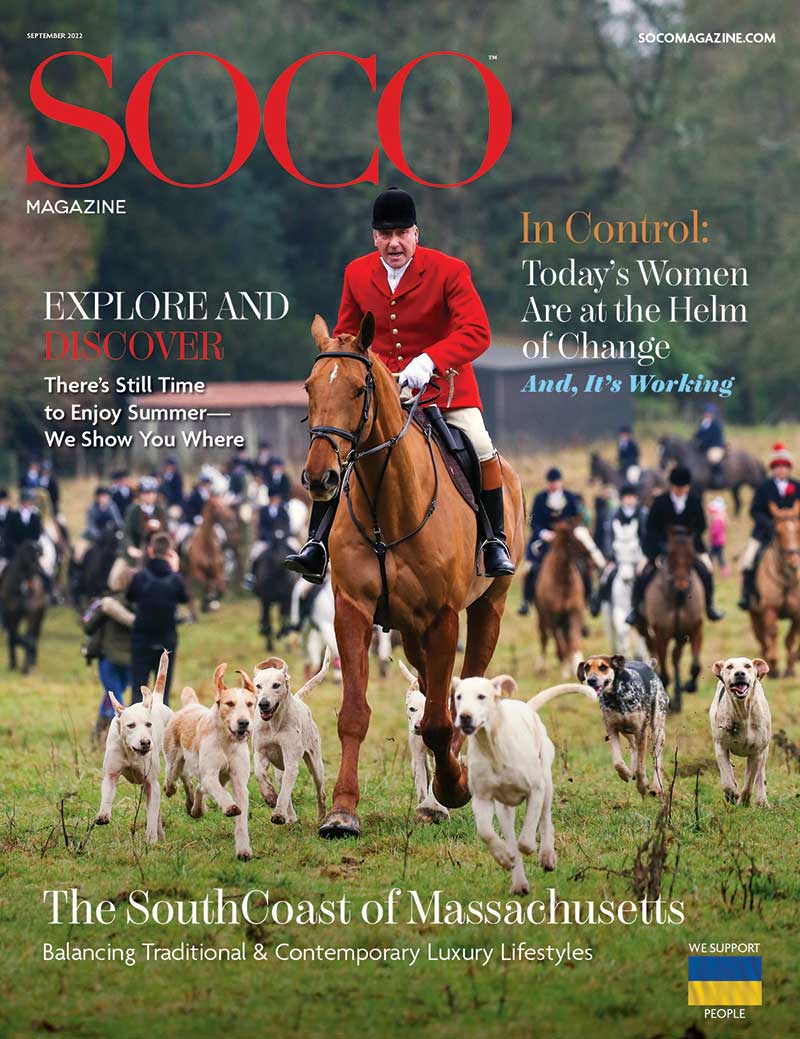

Click the cover above to receive a free digital subscription

Archives

June 2022

Categories

|