|

By Natalie Miller

Photo courtesy of LA2 In the early 1980s, the streets of New York were a playground for alternative artists and performers. Drawing inspiration from the subversive culture around them and the groundwork set by legends of the ‘60s and ‘70s, these hip-hop musicians, breakdancers, and graffiti artists created their way into the fabric of the city’s rich history. The graffiti culture, in particular, was thriving in New York subways and streets during this time, despite costly efforts by the city beginning in the ‘70s to manage the vandalism. Graffiti “tags” were all over the Big Apple as artists competed to write their signatures in as many places across the city as they could while avoiding police. One of the most recognizable tags in 1980 was that of LA2 (LAROC, LAII), a young Puerto Rican artist who started writing the name in junior high with markers on books, walls, and tables. The boy behind the name was 13-year-old Angel Ortiz, a Lower East Side native. As an early teen, Ortiz was encouraged by kids at the Boys Club to write his tag in the street, and it was there that he began to meet other graffiti artists. As he met more artists in the underground community, he moved from the street to New York subways, leaving his colorful tag in his wake. However, he didn’t stay in subways long. The streets were a more welcome canvas. “There was more freedom in the street,” recalls Ortiz, who still resides in Lower East Side Manhattan. Ortiz was also painting in his schoolyard as part of a club started by the school’s principal to deter kids from writing in books. It was there that he first met Keith Haring. Haring was an up-and-coming artist in his early twenties who was new to the city and had been trying to find Ortiz after seeing his tag all over the Lower East Side. Once Ortiz found out Haring was looking for him, he approached him at the schoolyard. Ortiz recalls that Haring was skeptical he was LA2—which stands for Little Angel—until Ortiz wrote his name for him right then and there. “He said, ‘I’ve been dying to meet you,’” says Ortiz. An Unlikely Pair That was the beginning of an unlikely but powerful collaboration. Over the next few years, Ortiz helped Haring elevate his paintings with the signature LA2 bold, high, and tight calligraphy style, and Haring ushered Ortiz into New York’s budding and eclectic art scene. “He wanted to get into graffiti,” recalls Ortiz of Haring, who was mostly painting characters and at the time was a relatively unknown artist from Pennsylvania. “Keith had no street cred. I gave him street cred. I got him into my world, and he introduced me to his world.” They combined their styles, and in 1982, the pair showed their first joint project at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York. On meeting Ortiz and the partnership, Haring then wrote: “I noticed his tags immediately… They stood out from the other graffiti. I could tell that this person, whoever it was, knew something about drawing that not everybody knows… On one of his visits to my studio, I invited him to tag on a primed yellow square I had prepared. The contrast between our lines was exciting. There is something uniquely satisfying to me in the fusion between our two styles of drawing. It is a delicate balance between the archaic and the extremely modern, classical, and psychedelic at the same time.” Haring quickly began to rise to prominence, and he brought young LA2 along with him. Haring introduced Ortiz to his friends: rapper and artist Fab 5 Freddy and artist Andy Warhol. During the six years they worked together, Ortiz met notable influencers such as Pee-wee Herman, Boy George, and Michael Jackson, and he traveled with Haring all over the world. Their collaborative show with Patti Astor’s FUN Gallery took them to Tokyo, London, and Italy. “We were just artists doing our thing,” says Ortiz. But what Ortiz didn’t think about at the time was the business aspects of his talent. He was young and unknowledgeable about how to navigate the fine art world. “At the time, us graffiti artists didn’t look at it as a business. It was our life, a way to express ourselves,” he recalls. “Keith was the businessman. I didn’t know how to communicate with people.” Ortiz says the duo had a verbal agreement, and even though galleries gave all the credit to Haring, he always made sure Ortiz got his share. Their collaboration ended in the late '80s once Haring, who was gay, began to take on a more political tone with his art, yet their friendship remained. Haring was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, and the following year he established the Keith Haring Foundation. By the time he died in 1990, Haring had become an iconic figure in the pop art world, and today his foundation continues to exhibit and sell his artwork. But the Foundation’s website makes no mention of Ortiz, and he has received no recognition or compensation for collaborated works since the death of Haring. Navigating the Art World Alone The years following his collaboration with Haring haven’t been as affluent for Ortiz, who is still doing what he’s been doing since he was 10: expressing himself through his art. Ortiz has battled with drug addiction but has continued to travel the world and exhibit his work. And despite being a big player in the influential 1980 graffiti scene, he remains mostly unknown and continues as a struggling artist. “He was one of the original graffiti artists,” says New York art collector Howard Shapiro. According to Shapiro, many in the art community knew of the Ortiz/Haring collaboration, but when the Foundation took over in the wake of Haring’s death, they wrote Ortiz out of the story. A teenager during the time of the collaboration, Ortiz didn’t take steps to ensure his work would be protected, and his career eclipsed, says Shapiro, who met Ortiz several years ago through a friend. “I am in the business and hadn’t heard of him,” says Shapiro. But once he saw his work, Shapiro was an instant fan and wanted to do a show. In July 2013, Shapiro’s Lawrence Fine Art studio in East Hampton held a solo exhibition of Ortiz’s work, entitled “LA Roc: Not Keith Haring” to considerable crowds. “The walls were bare,” says Shapiro, referencing the gallery walls at the close of the show. “We sold out. There was definitely a market for his work.” Over the next few years, Ortiz also showed at the Hampton Art Fair and several other venues, including the Museum of the City of New York and the Leila Heller Gallery. Heller first met Ortiz through Haring, and in 1984 the pair was part of her gallery’s “Calligraffiti” show along with several other artists. She continued to follow his career, and in 2013, her gallery hosted Part 2 of the “Calligraffiti” exhibition, which was curated by notable art dealer Jeffrey Deitch. She again called on Ortiz. “[Ortiz] had the entire front room of the gallery, and he made it into an installation,” she says. The success of that exhibition led to his solo show in Heller’s gallery later that year. Though she says the Haring collaboration was the most crucial part of his career, Ortiz was a central figure of the time and deserves to be recognized. Fighting for Recognition Ortiz says he is grateful to Haring, who taught him a lot about the art world. “I miss the guy,” says Ortiz. “He was the big brother I never had. He died too young.” With encouragement from those around him, Ortiz is currently working with the Foundation on an “amicable resolution” to regain the attribution he says is owed to him, says his fiancée Ramona Lugo. “[Haring] took care of Angel,” says Lugo. “The foundation is not giving Angel the credit he deserves.” Ortiz “was a fundamental part of the art of that era and people don’t know who he is,” says Shapiro. “And his work is being sold as Keith Haring’s.” While the collaboration was short, the dispute is valid, says Heller. “There are certain well-known pieces that are known collaborations [between Ortiz and Haring] because they were in shows.” Heller says if the Foundation attributes works as collaborations, it will change the value of the piece. Haring’s solo pieces sell for thousands to millions of dollars. A Keith Haring collaboration starts at $30,000 and goes up to a few $100,000, she explains, while Ortiz only brings in anywhere from $500 to $30,000. The conversation is ongoing, and there is yet to be a resolution between Ortiz and the Haring Foundation, which did not return phone calls for comment. Meanwhile, Ortiz, now in his early fifties, is continuing to create. This spring, he has plans to travel to London to do a show with British graffiti artist Stik, whom Ortiz hails as “a reincarnation of Keith.” “When it comes to history, they can’t erase it,” says Lugo. “Keith and Angel were huge influences on each other’s careers, and they had great respect for each other. Keith looked out for Angel, and Angel gave Keith the street credit he was looking for.” To learn more about Ortiz, aka LA2, visit la2graffitiartist.com.

3 Comments

Lucia Puca

5/4/2018 05:48:39

La2 is the best and one the first street artist

Reply

10/26/2020 01:31:30

Social media sites let brands gain attention if used right. Make the most of your social presence with these free social media marketing tools for business

Reply

11/15/2023 06:58:16

Great read! It's fascinating to explore the dynamics between artists and their influences. The question of whether Keith Haring borrowed from LA2's work adds another layer to the rich tapestry of artistic collaboration. Kudos for shedding light on this intriguing topic!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

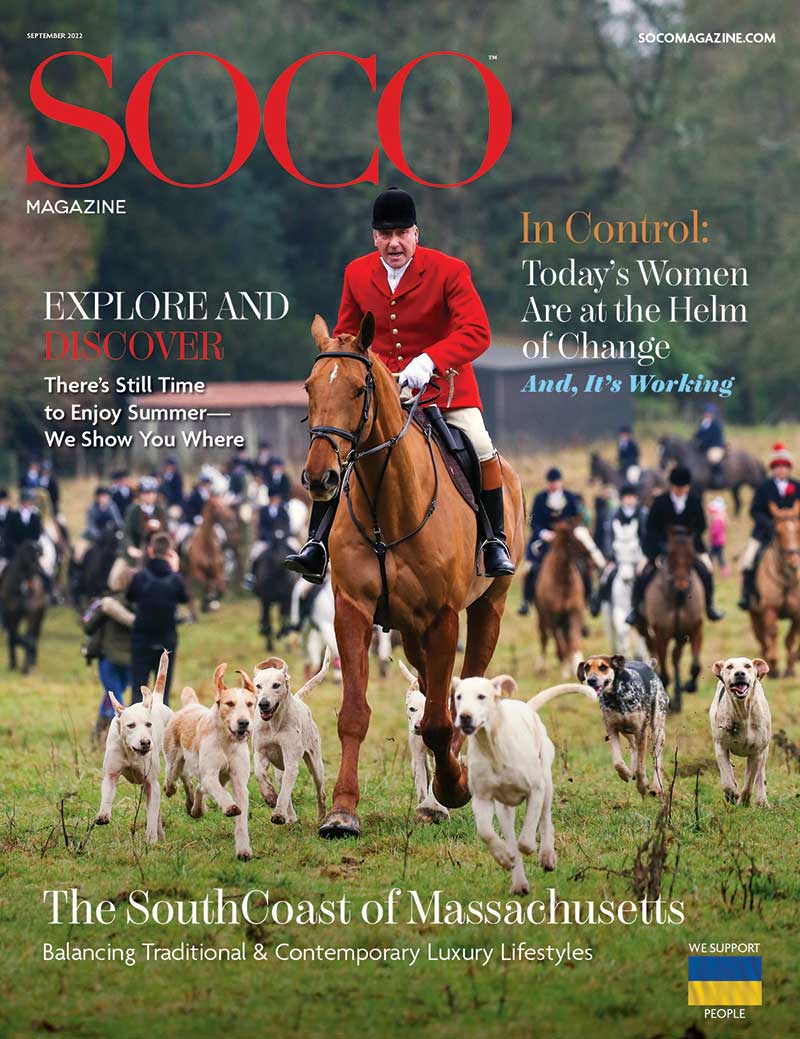

Click the cover above to receive a free digital subscription

Archives

June 2022

Categories

|